One of the dozens incredible predictions by J.G. Ballard. This comes from the 1977 essay “Future of the Future”, published on Vogue.

[via]

One of the dozens incredible predictions by J.G. Ballard. This comes from the 1977 essay “Future of the Future”, published on Vogue.

[via]

In this amazing lecture writer Kurt Vonnegut diagrams the shape of all stories: from Kafka’s “Metamorphosis” to “Cinderella”.

[via]

“For over a decade, a Chinese woman known as “Zhemao” created a massive, fantastical, and largely fictional alternate history of late Medieval Russia on Chinese Wikipedia, writing millions of words about entirely made-up political figures, massive (and fake) silver mines, and pivotal battles that never actually happened. She even went so far as to concoct details about things like currency and eating utensils.”

[more here]

I recently got an invitation to test the MidJourney beta, which is an amazing new AI app that generates images from text inputs. I’ve been playing with it for a while but I also spent hours just watching other people using it in a dedicated Discord server. It was a very funny and interesting experience and I got some amazing visual results, especially when I came up with the idea of feeding the algorithm a literary input instead of a merely descriptive sentence. Here are some images the app produced me based on some famous books incipits.

imagine/ The sky above the port was the color of television, tuned to a dead channel. – William Gibson, Neuromancer, 1984

imagine/ It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen. — George Orwell, 1984, 1949

imagine/ “Psychics can see the color of time it’s blue. – Ronald Sukenick, Blown Away, 1986

imagine/ Once upon a time , there was a woman who discovered she had turned into the wrong person. – Anne Tyler, Back When We Were Grownups, 2001

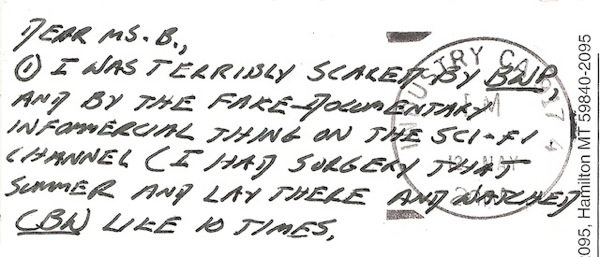

A portion of David Foster Wallace’s personal library now resides at the Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin. Maria Bustillos visited the Center and discovered clues to Wallace’s depression scribbled in the margins of several self-help books the writer owned and very carefully read…

One surprise was the number of popular self-help books in the collection, and the care and attention with which he read and reread them. I mean stuff of the best-sellingest, Oprah-level cheesiness and la-la reputation was to be found in Wallace’s library. Along with all the Wittgenstein, Husserl and Borges, he read John Bradshaw, Willard Beecher, Neil Fiore, Andrew Weil, M. Scott Peck and Alice Miller. Carefully.

Much of Wallace’s work has to do with cutting himself back down to size, and in a larger sense, with the idea that cutting oneself back down to size is a good one, for anyone (q.v., the Kenyon College commencement speech, later published as This is Water). I left the Ransom Center wondering whether one of the most valuable parts of Wallace’s legacy might not be in persuading us to put John Bradshaw on the same level with Wittgenstein. And why not; both authors are human beings who set out to be of some use to their fellows. It can be argued, in fact, that getting rid of the whole idea of special gifts, of the exceptional, and of genius, is the most powerful current running through all of Wallace’s work.

(Via kottke.org)

Fred Beneson wants to translate Herman Melville’s Moby Dick into emoji (emoticon for text messaging used in Japan). And he’s using Kickstarter to get the project funded..

Amy Casey dipinge case. Dipinge ammassi di case che si sforzano di diventare città. Ma rimangono cumuli di legno, ferro e cemento. Alcune sembrano appena atterrate, come astronavi, altre le ha portare un tornado, magari dal regno di Oz. Giurerei, però, di averne riconosciuta una, di queste città. E’ Ottavia:

Se volete credermi, bene. Ora dirò come è fatta Ottavia, città – ragnatela. C’è un precipizio in mezzo a due montagne scoscese: la città è sul vuoto, legata alle due creste con funi e catene e passerelle. Si cammina sulle traversine di legno, attenti a non mettereil piede negli intervalli, o ci si aggrappa alle maglie di canapa. Sotto non c’è niente per centinaia e centinaia di metri: qualche nuvola scorre; s’intravede più in basso il fondo del burrone. Questa è la base della città: una rete che serve da passaggio e da sostegno. Tutto il resto, invece d’elevarsi sopra, sta appeso sotto: scale di corda, amache, case fatte a sacco, attaccapanni, terrazzi come navicelle, otri d’acqua, becchi del gas, girarrosti, cesti appesi a spaghi, montacarichi, docce, trapezi e anelli per i giochi, teleferiche, lampadari, vasi con piante dal fogliame pendulo. Sospesa sull’abisso, la vita degli abitanti d’Ottavia è meno incerta che in altre città. Sanno che più di tanto la rete non regge.

(Italo Calvino, Le città invisibili)

1500 sedie vere invece, ammassate, sono più o meno così: